Microservices

As mentioned in the previous lesson, in the early days of software, applications were traditionally run on bare-metal hardware servers. Next, virtualized deployments with VMs were used. These solved the issue of portability somewhat, since you could package a virtual computer with a deterministic environment, and you could even install a few separate VMs on one physical computer to get more efficient bin-packing of app and resource isolation for security purposes. However, as previously mentioned, VMs are heavy - meaning they take up more system memory, hard disk space and CPU capacity. This never used to be a big issue since most applications were developed as monoliths.

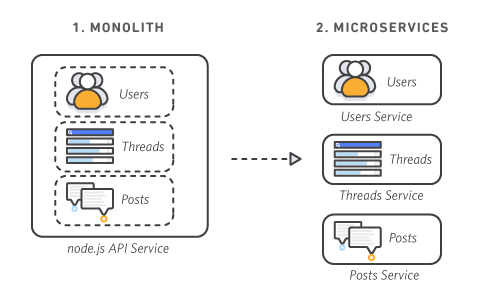

Monolithic vs. Microservices Architecture

Monoliths refer to a large piece of software that contains many different pieces of functionality, or tiers. for example a large eCommerce system, that has the ability to manage users, take payments, connect to databases, serve the front-end GUI, log debugging messages etc. Each individual piece of functionality will be tightly-coupled with one another through the way they interact with each other in the code (calling each others' functions, instantiating each other as objects etc.). The entire application would be deploy as one monolith, hence why a big VM wasn't a massive issue.

The problems with monoliths however, is that making rapid incremental changes to parts of the system becomes very difficult. Firstly, the build-times could be massive, so making small changes to one small part of the app and testing to see if it works as expected becomes prohibitive if the time it takes the app to compile can sometimes be in the hours. Also, since the app is so tightly-coupled, it's never clear if making a small change to one part may have catastrophic effects on another downstream part that depends on it.

Another issue is that each tier may be accessed at different frequencies. For example, the payment system may get many requests or require loads of resources, but the email alert system is rarely used. We can use service replication to add more replicas of the app and route some user requests to another server to reduce the load on the single server and allow more payments requests to get fulfilled. This however also replicates the email system because it's all combined into one. So you've got many replicas of a dormant part of the system taking up unnecessary resources.

Enter microservices. From AWS's documentation:

Microservices are an architectural and organizational approach to software development where software is composed of small independent services that communicate over well-defined APIs. These services are owned by small, self-contained teams.

Microservices architectures make applications easier to scale and faster to develop, enabling innovation and accelerating time-to-market for new features.

So in the eCommerce example, each tier would be its own separate self-contained microservice that exposes an API to other microservices to consume to use its functionality. Individual teams could then own each microservice and iterative quickly on small changes and improvements, as long as they keep to the previously agreed contract of how their API will work.

Also, in the payments vs. email system example, the payments container can be replicated to scale up and deal with the extra load, without needing to also replicate the email system, saving on cost (of the the hardware servers).

This advent of microservices developed alongside, and indeed influenced the adoption of agile methodology to create software products in small, iterative, incremental sprints.

Problems with Microservices and Containers Alone

So Containers made software portable and enabled microservice architecture, making it possible to package and deploy many lightweight applications alongside one another on a host machine, in an efficient, reliable and cost effective way. However, even though microservices solved some problems, they brought with them some of their own hurdles.

It became easier to make changes to individual parts of the system, but the complexity of a monolithic application does not disappear if it is re-implemented as a set of microservices. Some of the complexity gets translated into operational complexity. Now we have to consider networking, message format design, fault tolerance, and much more complicated deployment.

As we saw, Docker was great at deploying individual containers. But we also need a way to run large distributed systems resiliently with many containers that are able to scale individually and automatically; communicate with each other; and recover automatically if a service goes down. That's where Kubernetes comes in!